Introduction

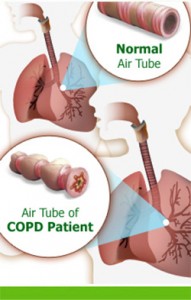

COPD is a serious, progressive lung disease that can make it difficult to breathe and get enough oxygen into the body. It can make simple activities like walking up the stairs or running daily errands challenging.

Symptoms

The most common symptom of COPD is shortness of breath. While it’s common to feel short of breath after physical exertion, simple everyday activities, such as getting dressed or walking up a few steps, can cause someone with COPD to feel seriously short of breath. Sometimes, people with COPD will knowingly or unknowingly limit their activity in an attempt to avoid feeling short of breath.

The most common symptom of COPD is shortness of breath. While it’s common to feel short of breath after physical exertion, simple everyday activities, such as getting dressed or walking up a few steps, can cause someone with COPD to feel seriously short of breath. Sometimes, people with COPD will knowingly or unknowingly limit their activity in an attempt to avoid feeling short of breath.

Other symptoms of COPD include :

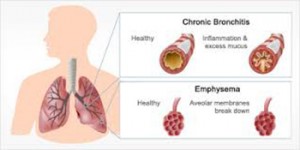

Frequent Cough : Everyone coughs from time to time, but a cough that lingers can be a symptom of chronic bronchitis and COPD. In fact, a cough that lasts at least 3 months a year for 2 consecutive years is the primary symptom of chronic bronchitis.

Cough with mucus (phlegm) : It’s normal to cough up mucus sometimes. But a continuously productive cough—a cough that regularly brings up mucus—can be a symptom of COPD.

Inability to maintain activity levels due to fatigue or shortness of breath : People with COPD can become less active over time. They may notice that they rest much more than they used to, or that they get less done in a day, due to the need to move slowly and rest.

Blueness of the lips or fingernail beds : A blue-tinge to the lips or fingernail area indicates a serious lack of adequate oxygen in the blood and can be a symptom of COPD.

Frequent colds and nose and throat infections : Chronic bronchitis (one of the diseases that make up COPD) causes excess mucus production in the airways. That excess mucus makes the body prone to upper respiratory infections.

Causes

The most common cause of COPD is long-term cigarette smoking. In fact, most cases of COPD are caused by smoking. Not everyone who smokes develops COPD, though, and not everyone with COPD has a history of smoking. Nonsmokers can get COPD too.

Additional causes of COPD include :

Exposure to work-related dusts and chemicals : Certain vapors, fumes, and dusts (such as coal dust and silica) can contribute to the development of COPD.

Indoor air pollution : According to the World Health Organization, nearly 3 billion people around the world cook their food and heat their homes with open fires or leaky stoves. These fires and stoves produce small soot particles that contribute to indoor air pollution and the development of COPD. Poorly ventilated homes increase the risk of serious indoor air pollution and COPD.

Secondhand Smoke : Some nonsmokers who develop cigarette-related COPD have been exposed to secondhand smoke. Many live with smokers or spent years working in smoke-filled environments, such as bars or restaurants.

Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency (also called Alpha-1) : This uncommon, inherited disorder increases the risk of lung and liver disease. Current guidelines recommend testing once for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in adults with symptomatic COPD regardless of smoking history. Alpha-1 can only be diagnosed with a blood test.

Childhood respiratory infection : Evidence suggests that colds and respiratory viruses in childhood, especially before age 2, may decrease lung function and increase the risk of developing breathing problems and COPD in adulthood.

Tests and Diagnosis

Your health-care provider will conduct a thorough physical exam and listen to your heart and lungs. He or she will observe your breathing, both at rest and after minimal activity (such as walking into the room). You will also be asked questions about your medical history. Some tests that might be used to further evaluate your breathing and health include:

Your health-care provider will conduct a thorough physical exam and listen to your heart and lungs. He or she will observe your breathing, both at rest and after minimal activity (such as walking into the room). You will also be asked questions about your medical history. Some tests that might be used to further evaluate your breathing and health include:

Breathing Tests : (also called pulmonary functions tests, PFTs, or spirometry). This pain-free test measures your lung function using a device called a spirometer. You breathe out into a mouthpiece, and the spirometer measures the amount of air(volume) and the speed of air(flow) you blow out.

Chest x-ray : A chest x-ray produces a picture of your heart and lungs. It can be used to rule out other lung problems and can detect some lung characteristics common to COPD. A chest x-ray alone can’t diagnose COPD, but it can offer your health-care provider important information.

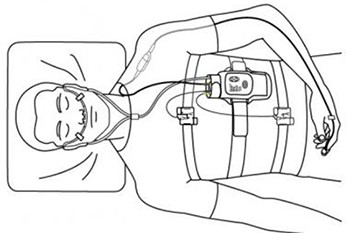

Oxygen Level Measurements : Your clinician can measure the level of oxygen in your blood with a simple device called a pulse oximeter. A pulse oximeter uses a clamp-shaped sensor that’s applied to a fingertip — don’t worry, it’s painless. The sensor emits a red-light and indicates the oxygen level in your body. Certain blood tests can also indicate the level of oxygen in your body.

Blood Tests : Blood tests can be used to check your oxygen level, to test for alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency (a rare genetic disorder that can cause COPD), and to check for infections.

Mucus (Phlegm or Sputum) Culture : If you’re coughing up any “gunk,” your health-care provider can send a sample to the lab for analysis. Lab tests can help detect infection and determine treatment.

Exercise Tests : An exercise test can help health-care providers understand how your body and breathing react to activity. The test typically takes place at a hospital or clinic, and a health-care provider will measure your breathing, heart activity, and oxygen levels before, during, and after exercise. You will be asked to ride a stationary bike or walk on a treadmill. A clinician will observe the test, which will end before you get too winded or tired.

Complications

COPD can cause or contribute to the development of several other serious health problems. Adequately treating and controlling COPD can decrease your risk of developing other health issues. Complications of COPD include :

COPD can cause or contribute to the development of several other serious health problems. Adequately treating and controlling COPD can decrease your risk of developing other health issues. Complications of COPD include :

Heart disease : Lack of oxygen in the body strains the heart and can lead to enlargement of the heart and heart failure. COPD also increases the risk of high blood pressure.

Respiratory infections : COPD increases your risk of contracting colds and lung infections. And underlying COPD increases the risk of a simple cold developing into something much more serious, such as pneumonia.

Lung cancer : COPD increases the risk of lung cancer in people who have smoked.

Depression : It can be difficult to adjust to any changes in your health, especially ones that make it more difficult for you to do the things you love. It’s common to feel depressed or down about a diagnosis of COPD. If your feelings of sadness last several weeks, though, or if you find you’re avoiding people and activity, or no longer feeling joy in life, let your health-care provider know. You could be experiencing clinical depression.

COPD Exacerbations : (flares of disease), are the most common complication of COPD. A COPD exacerbation is when your COPD suddenly gets worse. Most people with COPD have a fairly regular baseline, a degree of shortness of breath, fatigue, and coughing that is normal for them. During a COPD exacerbation, someone who has COPD may be much more short of breath, coughing much more than usual, or producing more sputum (mucus) than usual.

COPD exacerbations can land you in the hospital, so it’s important to take them seriously. Your health-care provider will work with you to develop a COPD action plan–a treatment plan you can use to head-off flares. Following your action plan can decrease the severity of your flare-up and keep you out of the hospital.

If your action plan doesn’t seem to be working–if your symptoms are getting worse instead of better–call your health-care provider right away.

Call 911 (or have someone else call 911) if you are extremely short of breath, if you have chest pain, or if your fingertips or lips are turning blue.

Preparing for your Appointment

Your doctor will want to know as much as possible about your overall health, your difficulties breathing, your family history, and your medications, so start gathering information well in advance of your appointment. Pulling together this information will help your health-care provider arrive at an accurate diagnosis and will make your appointment go more smoothly. Information you’ll want to gather includes the following:

A record of your health complaints : What is your breathing like on an everyday basis? Are there certain activities that make you more short of breath? Certain things that seem to help your breathing, or make it worse? Write it all down. You might want to consider keeping an activity log–a record of your activity, breathing, and fatigue–for a few days, as well.

A complete list of your medications, supplements, and vitamins : Include all prescription and over-the-counter medications and supplements, even herbal and natural remedies. If possible, bring the bottles and containers with you to your appointment so your health-care provider can see exactly what you’re taking.

A list of allergies : Your health-care provider will want to know any allergies you have, including allergies to medications, foods, environmental allergens such as pollen or pets, and latex. Be prepared to discuss your reaction and any current allergy exposure or treatment.

Your past medical history : Your health-care provider will be especially interested in any lung and breathing problems you’ve had in the past, as well as what treatments you underwent. If you have had previous tests such as breathing tests (spirometry or pulmonary function tests) or imaging of your lungs the results from your tests will be helpful. Also be prepared to discuss any other medical diagnoses or conditions you may have.

A record of your smoking/pollution exposure : Do you smoke? If so, when did you start? How many packs per day (or week) did you/do you smoke? Have you ever been exposed to secondhand smoke? Indoor air pollution? Do you or did you work in a smoke-, dust-, or chemical-filled environment?

Family history : Does anyone else in your family have a history of lung or breathing problems?

Questions : It’s a good idea to write down any questions you may have, so you don’t forget to ask them when you’re at your appointment.

Treatment

There is no cure for COPD, but treatment can help you control your symptoms, so you can enjoy life. Appropriate treatment will help you feel better and may help you live longer.

Medication is just part of the treatment of COPD. Your health-care provider will also talk to you about implementing lifestyle changes that will help you live better with COPD. Avoiding exposure to triggers (things that make your breathing worse), planning your activity, and using special breathing techniques to improve oxygen flow to your lungs can help you feel better. People with COPD benefit from more, rather than less exercise. Oxygen therapy can also be used to treat COPD. Your health-care provider will work with you to determine what combination of medications and interventions is most effective to control your COPD.

Because COPD is a progressive disease, your treatment plan will probably change over time. It’s important to see your health-care provider on a regular basis so that your treatment plan can be tweaked as needed.

Medications are used to open up the airways and improve the flow of air and oxygen to the body. COPD medications are generally divided into two main categories:

Maintenance Medications and Rescue Medications : Maintenance medications are those taken on a daily basis. They are the ones that help you maintain a “baseline.” They should be taken every day (whether or not you feel symptoms) and work to control symptoms over the long run.

Rescue medications are taken during COPD flare-ups or for immediate relief of symptoms. They are “sometimes” medications, to be used only when your breathing or COPD is bad. Your health-care provider will let you know when and under what conditions you should take your rescue medication(s).

A variety of medications can be used as maintenance or rescue medications. Some of the most common COPD medications are:

Bronchodilators : These are medications that dilate, or open up, the airways. They are usually given through an inhaler or nebulizer machine, but sometimes pills are used. There are both long-acting and short-acting bronchodilators. Long-acting bronchodilators may be used as maintenance medication. Short-acting bronchodilators are used as rescue medication.

Corticosteroids : Also known simply as “steroids,” these medications decrease inflammation and swelling and are used to keep the airways open in COPD. Steroids used to treat COPD are not the same as anabolic steroids, which are muscle-building steroids often misused by athletes and others. Steroids for COPD come in both pill and inhaler form and can be used as both maintenance and rescue medication.

Antibiotics : Antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections of the lungs. They are most commonly used during COPD exacerbations as part of your COPD action plan. Antibiotics are only effective against bacteria, so see your health-care provider as soon as you think you have an infection. He or she will try to figure out what’s causing the infection and order appropriate treatment.

It’s important to take all of your medication as prescribed. Your health-care provider and pharmacist will review your medications with you. Make sure you ask questions if you don’t understand what a medication is, what it’s used for, or when or how to take it.

Taking your medication properly is your responsibility. Here are some tips to help you:

- Organize your medication with a pill box, a chart, or around routine events like meals or brushing your teeth. This makes it easier to remember to take your medication and easier to tell if you’ve missed a dose!

- Do not skip your medication or skimp on your doses. Not taking the right amount of your medication can make your COPD worse and may result in an expensive hospitalization.

- Use inhalers and nebulizers properly so you get the full benefit of the medication. Your health-care provider will show you how to use your inhaler(s) and/or nebulizer.

Surgical Options for the Treatment of COPD Surgery to treat or control COPD may be an option for severe disease in very select patients. The two most common surgical treatments for COPD are lung volume reduction surgery and lung transplantation.

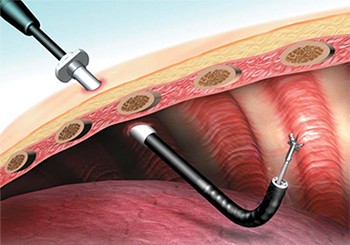

Lung Volume Reduction Surgery This surgery is used to remove diseased portions of one or both lungs. When these portions of the lung are removed, the volume of the lungs inside the rib cage is reduced, making it easier for people to breathe.

Because all surgeries include some risk, your health-care providers will carefully evaluate you to see if lung volume reduction surgery is a good choice for you.

Lung Transplantation A lung transplant replaces one or both diseased lungs with those of a donor.

- Be oxygen-dependent.

- Have severe COPD that no longer responds to medical treatment and may be fatal within 2 years.

- Be physically able to undergo the surgery and the treatment that follows.

- Usually be under the age of 65, but some centers will perform transplants on older patients.

Lung transplantation has many risks, and donor lungs are not easily available. Waiting for a donor lung can sometimes take 2 or more years. Also, after surgery, you will need to take many different medications for the rest of your life to prevent rejection of the transplanted lungs and to prevent infection.